Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning

Volodymyr Mnih and Koray Kavukcuoglu and David Silver and Alex Graves and Ioannis Antonoglou and Daan Wierstra and Martin Riedmiller

arXiv e-Print archive - 2013 via Local arXiv

Keywords: cs.LG

First published: 2013/12/19 (12 years ago)

Abstract: We present the first deep learning model to successfully learn control policies directly from high-dimensional sensory input using reinforcement learning. The model is a convolutional neural network, trained with a variant of Q-learning, whose input is raw pixels and whose output is a value function estimating future rewards. We apply our method to seven Atari 2600 games from the Arcade Learning Environment, with no adjustment of the architecture or learning algorithm. We find that it outperforms all previous approaches on six of the games and surpasses a human expert on three of them.

more

less

Volodymyr Mnih and Koray Kavukcuoglu and David Silver and Alex Graves and Ioannis Antonoglou and Daan Wierstra and Martin Riedmiller

arXiv e-Print archive - 2013 via Local arXiv

Keywords: cs.LG

First published: 2013/12/19 (12 years ago)

Abstract: We present the first deep learning model to successfully learn control policies directly from high-dimensional sensory input using reinforcement learning. The model is a convolutional neural network, trained with a variant of Q-learning, whose input is raw pixels and whose output is a value function estimating future rewards. We apply our method to seven Atari 2600 games from the Arcade Learning Environment, with no adjustment of the architecture or learning algorithm. We find that it outperforms all previous approaches on six of the games and surpasses a human expert on three of them.

|

[link]

* They use an implementation of Q-learning (i.e. reinforcement learning) with CNNs to automatically play Atari games.

* The algorithm receives the raw pixels as its input and has to choose buttons to press as its output. No hand-engineered features are used. So the model "sees" the game and "uses" the controller, just like a human player would.

* The model achieves good results on various games, beating all previous techniques and sometimes even surpassing human players.

### How

* Deep Q Learning

* *This is yet another explanation of deep Q learning, see also [this blog post](http://www.nervanasys.com/demystifying-deep-reinforcement-learning/) for longer explanation.*

* While playing, sequences of the form (`state1`, `action1`, `reward`, `state2`) are generated.

* `state1` is the current game state. The agent only sees the pixels of that state. (Example: Screen shows enemy.)

* `action1` is an action that the agent chooses. (Example: Shoot!)

* `reward` is the direct reward received for picking `action1` in `state1`. (Example: +1 for a kill.)

* `state2` is the next game state, after the action was chosen in `state1`. (Example: Screen shows dead enemy.)

* One can pick actions at random for some time to generate lots of such tuples. That leads to a replay memory.

* Direct reward

* After playing randomly for some time, one can train a model to predict the direct reward given a screen (we don't want to use the whole state, just the pixels) and an action, i.e. `Q(screen, action) -> direct reward`.

* That function would need a forward pass for each possible action that we could take. So for e.g. 8 buttons that would be 8 forward passes. To make things more efficient, we can let the model directly predict the direct reward for each available action, e.g. for 3 buttons `Q(screen) -> (direct reward of action1, direct reward of action2, direct reward of action3)`.

* We can then sample examples from our replay memory. The input per example is the screen. The output is the reward as a tuple. E.g. if we picked button 1 of 3 in one example and received a reward of +1 then our output/label for that example would be `(1, 0, 0)`.

* We can then train the model by playing completely randomly for some time, then sample some batches and train using a mean squared error. Then play a bit less randomly, i.e. start to use the action which the network thinks would generate the highest reward. Then train again, and so on.

* Indirect reward

* Doing the previous steps, the model will learn to anticipate the *direct* reward correctly. However, we also want it to predict indirect rewards. Otherwise, the model e.g. would never learn to shoot rockets at enemies, because the reward from killing an enemy would come many frames later.

* To learn the indirect reward, one simply adds the reward value of highest reward action according to `Q(state2)` to the direct reward.

* I.e. if we have a tuple (`state1`, `action1`, `reward`, `state2`), we would not add (`state1`, `action1`, `reward`) to the replay memory, but instead (`state1`, `action1`, `reward + highestReward(Q(screen2))`). (Where `highestReward()` returns the reward of the action with the highest reward according to Q().)

* By training to predict `reward + highestReward(Q(screen2))` the network learns to anticipate the direct reward *and* the indirect reward. It takes a leap of faith to accept that this will ever converge to a good solution, but it does.

* We then add `gamma` to the equation: `reward + gamma*highestReward(Q(screen2))`. `gamma` may be set to 0.9. It is a discount factor that devalues future states, e.g. because the world is not deterministic and therefore we can't exactly predict what's going to happen. Note that Q will automatically learn to stack it, e.g. `state3` will be discounted to `gamma^2` at `state1`.

* This paper

* They use the mentioned Deep Q Learning to train their model Q.

* They use a k-th frame technique, i.e. they let the model decide upon an action at (here) every 4th frame.

* Q is implemented via a neural net. It receives 84x84x4 grayscale pixels that show the game and projects that onto the rewards of 4 to 18 actions.

* The input is HxWx4 because they actually feed the last 4 frames into the network, instead of just 1 frame. So the network knows more about what things are moving how.

* The network architecture is:

* 84x84x4 (input)

* 16 convs, 8x8, stride 4, ReLU

* 32 convs, 4x4, stride 2, ReLU

* 256 fully connected neurons, ReLU

* <N_actions> fully connected neurons, linear

* They use a replay memory of 1 million frames.

### Results

* They ran experiments on the Atari games Beam Rider, Breakout, Enduro, Pong, Qbert, Seaquest and Space Invaders.

* Same architecture and hyperparameters for all games.

* Rewards were based on score changes in the games, i.e. they used +1 (score increases) and -1 (score decreased).

* Optimizer: RMSProp, Batch Size: 32.

* Trained for 10 million examples/frames per game.

* They had no problems with instability and their average Q value per game increased smoothly.

* Their method beats all other state of the art methods.

* They managed to beat a human player in games that required not so much "long" term strategies (the less frames the better).

* Video: starts at 46:05.

https://youtu.be/dV80NAlEins?t=46m05s

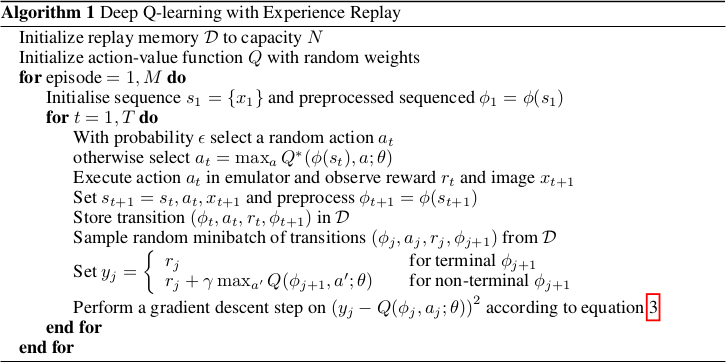

*The original full algorithm, as shown in the paper.*

--------------------

### Rough chapter-wise notes

* (1) Introduction

* Problems when using neural nets in reinforcement learning (RL):

* Reward signal is often sparse, noise and delayed.

* Often assumption that data samples are independent, while they are correlated in RL.

* Data distribution can change when the algorithm learns new behaviours.

* They use Q-learning with a CNN and stochastic gradient descent.

* They use an experience replay mechanism (i.e. memory) from which they can sample previous transitions (for training).

* They apply their method to Atari 2600 games in the Arcade Learning Environment (ALE).

* They use only the visible pixels as input to the network, i.e. no manual feature extraction.

* (2) Background

* blablabla, standard deep q learning explanation

* (3) Related Work

* TD-Backgammon: "Solved" backgammon. Worked similarly to Q-learning and used a multi-layer perceptron.

* Attempts to copy TD-Backgammon to other games failed.

* Research was focused on linear function approximators as there were problems with non-linear ones diverging.

* Recently again interest in using neural nets for reinforcement learning. Some attempts to fix divergence problems with gradient temporal-difference methods.

* NFQ is a very similar method (to the one in this paper), but worked on the whole batch instead of minibatches, making it slow. It also first applied dimensionality reduction via autoencoders on the images instead of training on them end-to-end.

* HyperNEAT was applied to Atari games and evolved a neural net for each game. The networks learned to exploit design flaws.

* (4) Deep Reinforcement Learning

* They want to connect a reinforcement learning algorithm with a deep neural network, e.g. to get rid of handcrafted features.

* The network is supposes to run on the raw RGB images.

* They use experience replay, i.e. store tuples of (pixels, chosen action, received reward) in a memory and use that during training.

* They use Q-learning.

* They use an epsilon-greedy policy.

* Advantages from using experience replay instead of learning "live" during game playing:

* Experiences can be reused many times (more efficient).

* Samples are less correlated.

* Learned parameters from one batch don't determine as much the distributions of the examples in the next batch.

* They save the last N experiences and sample uniformly from them during training.

* (4.1) Preprocessing and Model Architecture

* Raw Atari images are 210x160 pixels with 128 possible colors.

* They downsample them to 110x84 pixels and then crop the 84x84 playing area out of them.

* They also convert the images to grayscale.

* They use the last 4 frames as input and stack them.

* So their network input has shape 84x84x4.

* They use one output neuron per possible action. So they can compute the Q-value (expected reward) of each action with one forward pass.

* Architecture: 84x84x4 (input) => 16 8x8 convs, stride 4, ReLU => 32 4x4 convs stride 2 ReLU => fc 256, ReLU => fc N actions, linear

* 4 to 18 actions/outputs (depends on the game).

* Aside from the outputs, the architecture is the same for all games.

* (5) Experiments

* Games that they played: Beam Rider, Breakout, Enduro, Pong, Qbert, Seaquest, Space Invaders

* They use the same architecture und hyperparameters for all games.

* They give a reward of +1 whenever the in-game score increases and -1 whenever it decreases.

* They use RMSProp.

* Mini batch size was 32.

* They train for 10 million frames/examples.

* They initialize epsilon (in their epsilon greedy strategy) to 1.0 and decrease it linearly to 0.1 at one million frames.

* They let the agent decide upon an action at every 4th in-game frame (3rd in space invaders).

* (5.1) Training and stability

* They plot the average reward und Q-value per N games to evaluate the agent's training progress,

* The average reward increases in a noisy way.

* The average Q value increases smoothly.

* They did not experience any divergence issues during their training.

* (5.2) Visualizating the Value Function

* The agent learns to predict the value function accurately, even for rather long sequences (here: ~25 frames).

* (5.3) Main Evaluation

* They compare to three other methods that use hand-engineered features and/or use the pixel data combined with significant prior knownledge.

* They mostly outperform the other methods.

* They managed to beat a human player in three games. The ones where the human won seemed to require strategies that stretched over longer time frames.

Your comment:

|

You must log in before you can submit this summary! Your draft will not be saved!

Preview: