|

Welcome to ShortScience.org! |

|

- ShortScience.org is a platform for post-publication discussion aiming to improve accessibility and reproducibility of research ideas.

- The website has 1584 public summaries, mostly in machine learning, written by the community and organized by paper, conference, and year.

- Reading summaries of papers is useful to obtain the perspective and insight of another reader, why they liked or disliked it, and their attempt to demystify complicated sections.

- Also, writing summaries is a good exercise to understand the content of a paper because you are forced to challenge your assumptions when explaining it.

- Finally, you can keep up to date with the flood of research by reading the latest summaries on our Twitter and Facebook pages.

Generating Images with Perceptual Similarity Metrics based on Deep Networks

Alexey Dosovitskiy and Thomas Brox

arXiv e-Print archive - 2016 via Local arXiv

Keywords: cs.LG, cs.CV, cs.NE

First published: 2016/02/08 (10 years ago)

Abstract: Image-generating machine learning models are typically trained with loss functions based on distance in the image space. This often leads to over-smoothed results. We propose a class of loss functions, which we call deep perceptual similarity metrics (DeePSiM), that mitigate this problem. Instead of computing distances in the image space, we compute distances between image features extracted by deep neural networks. This metric better reflects perceptually similarity of images and thus leads to better results. We show three applications: autoencoder training, a modification of a variational autoencoder, and inversion of deep convolutional networks. In all cases, the generated images look sharp and resemble natural images.

more

less

Alexey Dosovitskiy and Thomas Brox

arXiv e-Print archive - 2016 via Local arXiv

Keywords: cs.LG, cs.CV, cs.NE

First published: 2016/02/08 (10 years ago)

Abstract: Image-generating machine learning models are typically trained with loss functions based on distance in the image space. This often leads to over-smoothed results. We propose a class of loss functions, which we call deep perceptual similarity metrics (DeePSiM), that mitigate this problem. Instead of computing distances in the image space, we compute distances between image features extracted by deep neural networks. This metric better reflects perceptually similarity of images and thus leads to better results. We show three applications: autoencoder training, a modification of a variational autoencoder, and inversion of deep convolutional networks. In all cases, the generated images look sharp and resemble natural images.

|

[link]

* The authors define in this paper a special loss function (DeePSiM), mostly for autoencoders.

* Usually one would use a MSE of euclidean distance as the loss function for an autoencoder. But that loss function basically always leads to blurry reconstructed images.

* They add two new ingredients to the loss function, which results in significantly sharper looking images.

### How

* Their loss function has three components:

* Euclidean distance in image space (i.e. pixel distance between reconstructed image and original image, as usually used in autoencoders)

* Euclidean distance in feature space. Another pretrained neural net (e.g. VGG, AlexNet, ...) is used to extract features from the original and the reconstructed image. Then the euclidean distance between both vectors is measured.

* Adversarial loss, as usually used in GANs (generative adversarial networks). The autoencoder is here treated as the GAN-Generator. Then a second network, the GAN-Discriminator is introduced. They are trained in the typical GAN-fashion. The loss component for DeePSiM is the loss of the Discriminator. I.e. when reconstructing an image, the autoencoder would learn to reconstruct it in a way that lets the Discriminator believe that the image is real.

* Using the loss in feature space alone would not be enough as that tends to lead to overpronounced high frequency components in the image (i.e. too strong edges, corners, other artefacts).

* To decrease these high frequency components, a "natural image prior" is usually used. Other papers define some function by hand. This paper uses the adversarial loss for that (i.e. learns a good prior).

* Instead of training a full autoencoder (encoder + decoder) it is also possible to only train a decoder and feed features - e.g. extracted via AlexNet - into the decoder.

### Results

* Using the DeePSiM loss with a normal autoencoder results in sharp reconstructed images.

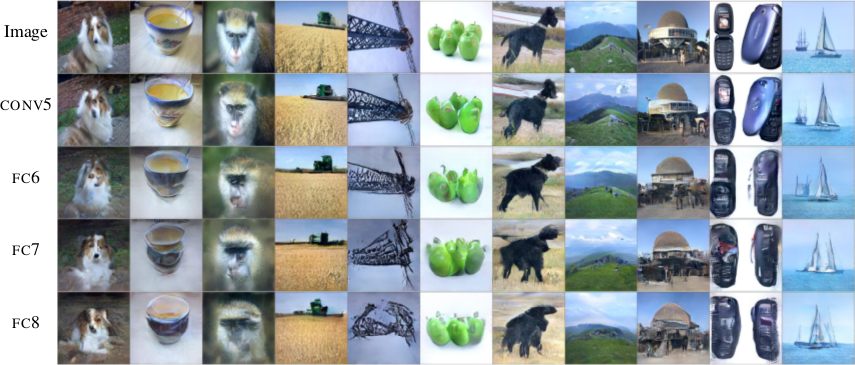

* Using the DeePSiM loss with a VAE to generate ILSVRC-2012 images results in sharp images, which are locally sound, but globally don't make sense. Simple euclidean distance loss results in blurry images.

* Using the DeePSiM loss when feeding only image space features (extracted via AlexNet) into the decoder leads to high quality reconstructions. Features from early layers will lead to more exact reconstructions.

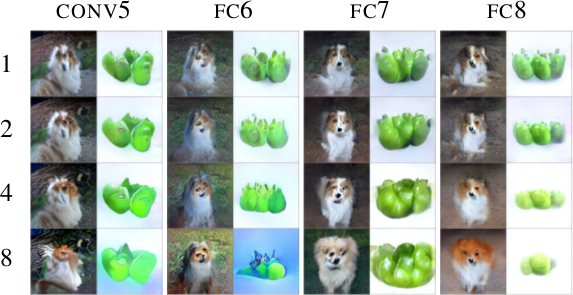

* One can again feed extracted features into the network, but then take the reconstructed image, extract features of that image and feed them back into the network. When using DeePSiM, even after several iterations of that process the images still remain semantically similar, while their exact appearance changes (e.g. a dog's fur color might change, counts of visible objects change).

*Images generated with a VAE using DeePSiM loss.*

*Images reconstructed from features fed into the network. Different AlexNet layers (conv5 - fc8) were used to generate the features. Earlier layers allow more exact reconstruction.*

*First, images are reconstructed from features (AlexNet, layers conv5 - fc8 as columns). Then, features of the reconstructed images are fed back into the network. That is repeated up to 8 times (rows). Images stay semantically similar, but their appearance changes.*

--------------------

### Rough chapter-wise notes

* (1) Introduction

* Using a MSE of euclidean distances for image generation (e.g. autoencoders) often results in blurry images.

* They suggest a better loss function that cares about the existence of features, but not as much about their exact translation, rotation or other local statistics.

* Their loss function is based on distances in suitable feature spaces.

* They use ConvNets to generate those feature spaces, as these networks are sensitive towards important changes (e.g. edges) and insensitive towards unimportant changes (e.g. translation).

* However, naively using the ConvNet features does not yield good results, because the networks tend to project very different images onto the same feature vectors (i.e. they are contractive). That leads to artefacts in the generated images.

* Instead, they combine the feature based loss with GANs (adversarial loss). The adversarial loss decreases the negative effects of the feature loss ("natural image prior").

* (3) Model

* A typical choice for the loss function in image generation tasks (e.g. when using an autoencoders) would be squared euclidean/L2 loss or L1 loss.

* They suggest a new class of losses called "DeePSiM".

* We have a Generator `G`, a Discriminator `D`, a feature space creator `C` (takes an image, outputs a feature space for that image), one (or more) input images `x` and one (or more) target images `y`. Input and target image can be identical.

* The total DeePSiM loss is a weighted sum of three components:

* Feature loss: Squared euclidean distance between the feature spaces of (1) input after fed through G and (2) the target image, i.e. `||C(G(x))-C(y)||^2_2`.

* Adversarial loss: A discriminator is introduced to estimate the "fakeness" of images generated by the generator. The losses for D and G are the standard GAN losses.

* Pixel space loss: Classic squared euclidean distance (as commonly used in autoencoders). They found that this loss stabilized their adversarial training.

* The feature loss alone would create high frequency artefacts in the generated image, which is why a second loss ("natural image prior") is needed. The adversarial loss fulfills that role.

* Architectures

* Generator (G):

* They define different ones based on the task.

* They all use up-convolutions, which they implement by stacking two layers: (1) a linear upsampling layer, then (2) a normal convolutional layer.

* They use leaky ReLUs (alpha=0.3).

* Comparators (C):

* They use variations of AlexNet and Exemplar-CNN.

* They extract the features from different layers, depending on the experiment.

* Discriminator (D):

* 5 convolutions (with some striding; 7x7 then 5x5, afterwards 3x3), into average pooling, then dropout, then 2x linear, then 2-way softmax.

* Training details

* They use Adam with learning rate 0.0002 and normal momentums (0.9 and 0.999).

* They temporarily stop the discriminator training when it gets too good.

* Batch size was 64.

* 500k to 1000k batches per training.

* (4) Experiments

* Autoencoder

* Simple autoencoder with an 8x8x8 code layer between encoder and decoder (so actually more values than in the input image?!).

* Encoder has a few convolutions, decoder a few up-convolutions (linear upsampling + convolution).

* They train on STL-10 (96x96) and take random 64x64 crops.

* Using for C AlexNet tends to break small structural details, using Exempler-CNN breaks color details.

* The autoencoder with their loss tends to produce less blurry images than the common L2 and L1 based losses.

* Training an SVM on the 8x8x8 hidden layer performs significantly with their loss than L2/L1. That indicates potential for unsupervised learning.

* Variational Autoencoder

* They replace part of the standard VAE loss with their DeePSiM loss (keeping the KL divergence term).

* Everything else is just like in a standard VAE.

* Samples generated by a VAE with normal loss function look very blurry. Samples generated with their loss function look crisp and have locally sound statistics, but still (globally) don't really make any sense.

* Inverting AlexNet

* Assume the following variables:

* I: An image

* ConvNet: A convolutional network

* F: The features extracted by a ConvNet, i.e. ConvNet(I) (feaures in all layers, not just the last one)

* Then you can invert the representation of a network in two ways:

* (1) An inversion that takes an F and returns roughly the I that resulted in F (it's *not* key here that ConvNet(reconstructed I) returns the same F again).

* (2) An inversion that takes an F and projects it to *some* I so that ConvNet(I) returns roughly the same F again.

* Similar to the autoencoder cases, they define a decoder, but not encoder.

* They feed into the decoder a feature representation of an image. The features are extracted using AlexNet (they try the features from different layers).

* The decoder has to reconstruct the original image (i.e. inversion scenario 1). They use their DeePSiM loss during the training.

* The images can be reonstructed quite well from the last convolutional layer in AlexNet. Chosing the later fully connected layers results in more errors (specifially in the case of the very last layer).

* They also try their luck with the inversion scenario (2), but didn't succeed (as their loss function does not care about diversity).

* They iteratively encode and decode the same image multiple times (probably means: image -> features via AlexNet -> decode -> reconstructed image -> features via AlexNet -> decode -> ...). They observe, that the image does not get "destroyed", but rather changes semantically, e.g. three apples might turn to one after several steps.

* They interpolate between images. The interpolations are smooth.

|

The Shattered Gradients Problem: If resnets are the answer, then what is the question?

Balduzzi, David and Frean, Marcus and Leary, Lennox and Lewis, J. P. and Ma, Kurt Wan-Duo and McWilliams, Brian

International Conference on Machine Learning - 2017 via Local Bibsonomy

Keywords: dblp

Balduzzi, David and Frean, Marcus and Leary, Lennox and Lewis, J. P. and Ma, Kurt Wan-Duo and McWilliams, Brian

International Conference on Machine Learning - 2017 via Local Bibsonomy

Keywords: dblp

|

[link]

Imagine you make a neural network mapping a scalar to a scalar. After you initialise this network in the traditional way, randomly with some given variance, you could take the gradient of the input with respect to the output for all reasonable values (between about - and 3 because networks typically assume standardised inputs). As the value increases, different rectified linear units in the network will randomly switch on, drawing a random walk in the gradients; another name for which is brown noise.

However, do the same thing for deep networks, and any traditional initialisation you choose, and you'll see the random walk start to look like white noise. One intuition given in the paper is that as different rectifiers in the network switch off and on the input is taking a number of different paths though the network. The number of possible paths grows exponentially with the depth of the network, so as the input varies, the gradients become increasingly chaotic. **The explanations and derivations given in the paper are much better reasoned and thorough, please read those if you are interested**.

Why should we care about this? Because the authors take the recent nonlinearity [CReLU][] (output is concatenation of `relu(x)` and `relu(-x)`) and develop an initialisation that will avoid problems with gradient shattering. The initialisation is just to take your standard initialised weight matrix $\mathbf{W}$ and set the right half to be the negative of the left half ($\mathbf{W}_{\text{left}}$). As long as the input to the layer is also concatenated, the left half will be multiplied by `relu(x)` and the right by `relu(-x)`. Then:

$$

\mathbf{W}.\text{CReLU}(\mathbf{x}) = \begin{cases} \mathbf{W}_{\text{left}}\mathbf{x} & \text{ if } x > 0 \\ \mathbf{W}_{\text{left}}\mathbf{x} & \text{ if } x \leq 0\end{cases}

$$

Doing this allows them to train deep networks without skip connections, and they show results on CIFAR-10 with depths of up to 200 exceeding (slightly) a similar resnet.

[crelu]: https://arxiv.org/abs/1603.05201

|

Effective deep learning training for single-image super-resolution in endomicroscopy exploiting video-registration-based reconstruction

Ravì, Daniele and Szczotka, Agnieszka Barbara and Shakir, Dzhoshkun Ismail and Pereira, Stephen P. and Vercauteren, Tom

arXiv e-Print archive - 2018 via Local Bibsonomy

Keywords: dblp

Ravì, Daniele and Szczotka, Agnieszka Barbara and Shakir, Dzhoshkun Ismail and Pereira, Stephen P. and Vercauteren, Tom

arXiv e-Print archive - 2018 via Local Bibsonomy

Keywords: dblp

|

[link]

Main purpose: * This work proposes a software-based resolution augmentation method which is more agile and simpler to implement than hardware engineering solutions. * The paper examines three deep learning single image super resolution techniques on pCLE images * A video-registration based method is proposed to estimate ground truth HR pCLE images (this can be assumed as the main objective of the paper) Highlights: * The papers emphasise that this is the first work to address the image resolution problem in pCLE image acquisitions * The paper introduces useful information on how pCLE devices work * Strong related work * Clear story * Comprehensive evaluation Main Idea: * Use video-registration based techniques to estimate the HR images (real ground truth HR image is not available) * Simulate LR images from estimate HR images with help of Voronoi diagram and Delaunay-based linear interpolation. * Train an Exemplar-based SR model (EBSR -- DL-based approach) to learn the mapping between simulated LR and estimate HR images. Methodology Details * To estimate the HR images, a video-registration based mosaicking techniques (by the same authors in MIA 2006) is used which fuses a collection of input images by averaging the temporal information. * Since mosaicking generates single large filed-of-view mosaic image from LR images, the mosaic-to-image diffeomorphic spatial transformation is used which results from the mosaicking process to propagate and crop the fused information from the mosaic back into each input LR image space. * At this point, the authors observe that the misalignment between input LR images (used in the video-registration based mosaicking technique) and estimate HR cause training problem for the EBSR model. So, they treat the HR images as realistic and chose to simulate LR images from them!!!! * Simulated LR images by obtained using the Voronoi diagram (averaging the Voronoi cell on HR image) + additive noise on estimate HR images. * Finally, they build to experimental datasets 1) LR_org and HR and 2) LR_synth and HR and train three CNN SR models on these twor datasets. * They train FSRCNN, EDSR, SRGAN * The networks are trained using L1+SSIM loss functions Experiment Notes: * SSIM and GCF are used to quantitatively assess the performance of the models. * A composite score is also used to take SSIM and GCF into account jointly * In the ideal case, when the models are trained and etsted on simulated LR and HR images, the quantitative results are convincing. * "From this experiment, it is possible to conclude that the proposed solution is capable of performing SR reconstruction when the models are trained on synthetic data with no domain gap at test time" * When models are trained and tested on original LR and estimate HR images, the performance is not reasonable * When the models are trained on simulated LR images and tested on original LR images, the results become better compared to the previous case, * For a solid conclusion, and MOS study was carried out. The models are trained on simulated LR images.  |

Net2Net: Accelerating Learning via Knowledge Transfer

Chen, Tianqi and Goodfellow, Ian J. and Shlens, Jonathon

arXiv e-Print archive - 2015 via Local Bibsonomy

Keywords: dblp

Chen, Tianqi and Goodfellow, Ian J. and Shlens, Jonathon

arXiv e-Print archive - 2015 via Local Bibsonomy

Keywords: dblp

|

[link]

This paper presents an approach to initialize a neural network from the parameters of a smaller and previously trained neural network. This is effectively done by increasing the size (in width and/or depth) of the previously trained neural network, in such of a way that the function represented by the network doesn't change (i.e. the output of the larger neural network is still the same). The motivation here is that initializing larger neural networks in this way allows to accelerate their training, since at initialization the neural network will already be quite good. In a nutshell, neural networks are made wider by adding several copies (selected randomly) of the same hidden units to the hidden layer, for each hidden layer. To ensure that the neural network output remains the same, each incoming connection weight must also be divided by the number of replicas that unit is connected to in the previous layer. If not training using dropout, it is also recommended to add some noise to this initialization, in order to break its initial symmetry (though this will actually break the property that the network's output is the same). As for making a deeper network, layers are added by initializing them to be the identity function. For ReLU units, this is achieved using an identity matrix as the connection weight matrix. For units based on sigmoid or tanh activations, unfortunately it isn't possible to add such identity layers. In their experiments on ImageNet, the authors show that this initialization allows them to train larger networks faster than if trained from random initialization. More importantly, they were able to outperform their previous validation set ImageNet accuracy by initializing a very large network from their best Inception network.  |

Adversarial Autoencoders

Makhzani, Alireza and Shlens, Jonathon and Jaitly, Navdeep and Goodfellow, Ian J.

arXiv e-Print archive - 2015 via Local Bibsonomy

Keywords: dblp

Makhzani, Alireza and Shlens, Jonathon and Jaitly, Navdeep and Goodfellow, Ian J.

arXiv e-Print archive - 2015 via Local Bibsonomy

Keywords: dblp

|

[link]

#### Summary of this post:

* an overview the motivation behind adversarial autoencoders and how they work * a discussion on whether the adversarial training is necessary in the first place. tl;dr: I think it's an overkill and I propose a simpler method along the lines of kernel moment matching.

#### Adversarial Autoencoders

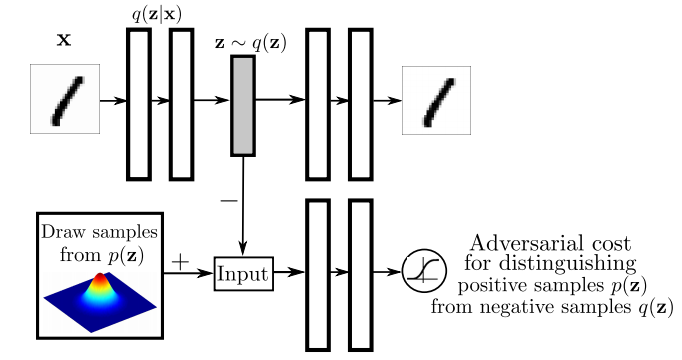

Again, I recommend everyone interested to read the actual paper, but I'll attempt to give a high level overview the main ideas in the paper. I think the main figure from the paper does a pretty good job explaining how Adversarial Autoencoders are trained:

The top part of this image is a probabilistic autoencoder. Given the input $\mathbf{x}$, some latent code $\mathbf{z}$ is generated by sampling from an encoding distribution $q(\mathbf{z}\vert\mathbf{x})$. This distribution is typically modeled as the output a deep neural network. In normal autoencoders this encoder would be deterministic, now we allow it to be probabilistic.

A decoder network is then trained to decode $\mathbf{z}$ and reconstruct the original input $\mathbf{x}$. Of course, reconstruction will not be perfect, but we train the networks to minimise reconstruction error, this is typically just mean squared error.

The reconstruction cost ensures that the encoding process retains information about the input image, but it doesn't enforce anything else about what these latent representations $\mathbf{z}$ should do. In general, their distribution is described as the aggregate posterior $q(\mathbf{z})=\mathbb{E}_\mathbf{x} q(\mathbf{z}\vert\mathbf{x})$. Often, we would like this distribution to match a certain prior $p(\mathbf{z})$. For example. we may want $\mathbf{z}$ to have independent components and Gaussian distributed (nonlinear ICA,PCA). Or we may want to force the latent representations to correspond to discrete class labels, or binary factors. Or we may simply want to ensure there are 'no gaps' in the latent space, and any random $\mathbf{z}$ would lead to a viable sample when squashed through the decoder network.

So there are multiple reasons why one might want to control the aggregate posterior $q(\mathbf{z})$ to match a predefined prior $p(\mathbf{z})$. The authors achieve this by introducing an additional term in the autoencoder loss function, one that measures the divergence between $q$ and $p$. The authors chose to do this via adversarial training: they train a discriminator network that constantly learns to discriminate between real code vectors $\mathbb{z}$ produced by encoding real data, and random code vectors sampled from $p$. If $q$ matches $p$ perfectly, the optimal discriminator network should have a large classification error.

#### Is this an overkill?

My main question about this paper was whether the adversarial cost is really needed here, because I think it's an overkill. Let me explain:

Adversarial training is powerful when all else fails to quantify divergence between complicated, potentially degenerate distributions in high dimensions, such as images or video. Our toolkit for dealing with images is limited, CNNs are the best tool we have, so it makes sense to incorporate them in training generative models for images. GANs - when applied directly to images - are a great idea.

However, here adversarial training is applied to an easier problem: to quantify the divergence between a simple, fixed prior (e.g. Gaussian) and an empirical distribution of latents. The latent space is usually lower-dimensional, distributions better behaved. Therefore, matching to $p(\mathbf{z})$ in latent space should be considerably easier than matching distributions over images.

Adversarial training makes no assumptions about the distributions compared, other than sampling from them. This comes very handy when both $p$ and $q$ are nasty such as in the generative adversarial network scenario: there, $p$ is the distribution of natural images, $q$ is a super complicated, degenerate distribution produced by squashing noise through a deep convnet. The price we pay for this flexibility is this: when $p$ or $q$ are actually easy to work with, adversarial training cannot exploit that, it still has to sample. (it would be interesting to see if expectations over $p(\mathbf{z})$ could be computed analytically). So even though in this work $p$ is as simple as a mixture of ten 2D Gaussians, we need to approximate everything by drawing samples.

#### Other things might work: kernel moment matching

Why can’t one use easier divergences? For example, I think moment matching based on kernel MMD would work brilliantly in this scenario. It would have the following advantages over the adversarial cost.

- closed form expressions: Depending on the choice of the prior $p(\mathbf{z})$ and kernel used in MMD, the expectations over $p$ may be available in closed form, without sampling. So for example if we use a squared exponential kernel and a mixture of Gaussians as $p$, the divergence from $p$ can be precomputed in closed form that is easy to evaluate.

- no nasty inner loop: Adversarial training requires the discriminator network to be reoptimised every time the generative model changes. So we end up with a gradient descent in the inner loop of a gradient descent, which is anything but nice to work with. This is why it takes so long to get it working, the whole thing is pretty unstable. In contrast, to evaluate MMD, the inner loop is not needed. In fact, MMD can also be thought of as the solution to a convex maximisation problem, but via the kernel trick the maximum has a closed form solution.

- the problem is well suited for MMD: because the distributions are smooth, and the space is nice and low-dimensional, MMD might work very well. Kernel-based methods struggle with complicated manifold-like structure of natural images, so I wouldn't expect MMD to be competitive with adversarial training if it is applied directly in the image space. Therefore, I actually prefer generative adversarial networks to generative moment matching networks. However, here we have an easier problem, simpler space, simpler distributions where MMD shines, and adversarial training is just not needed.

|